Exhibit Details

Open JanNov 2025

- Can you time travel with scent?

- Delve deeper

Memory connects our brains to time, blending past, present, and future. We pull past experiences into the present, form new memories, and research suggests we use the same pathways to recall the past that we do to imagine the future. Our perception of time is shaped by memory.

Some memories need cues to be triggered. You’ve likely experienced the “tip of the tongue” moment when a memory won’t come to mind but eventually surfaces with a prompt. This process, known as ecphory, is often triggered by familiar cues like sounds or smells.

Smells, in particular, are powerful memory cues. A familiar scent can instantly bring back vivid memories and emotions.

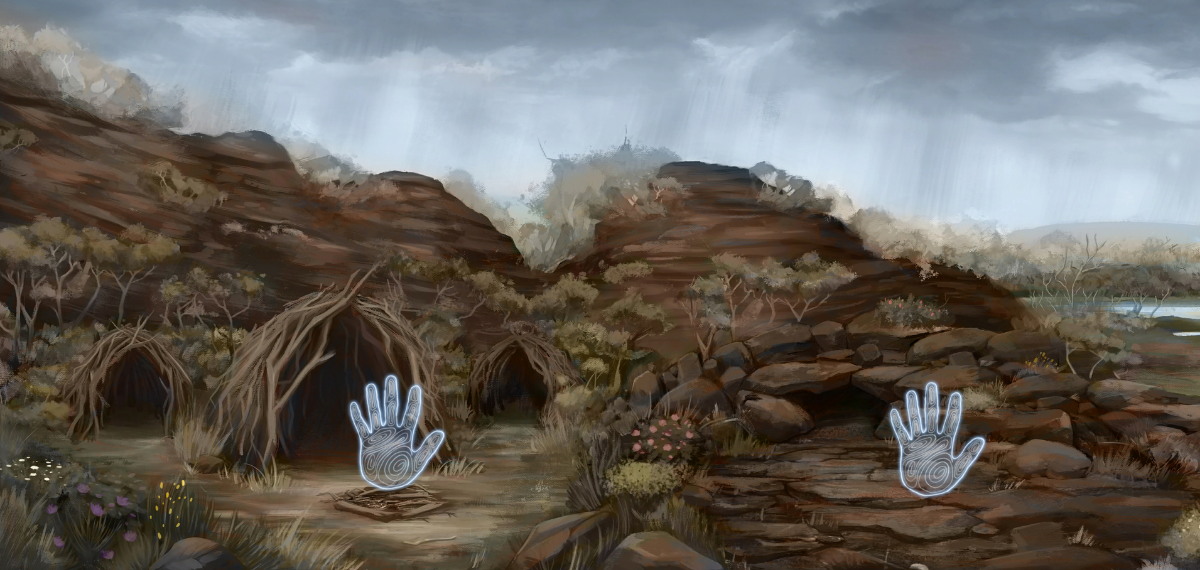

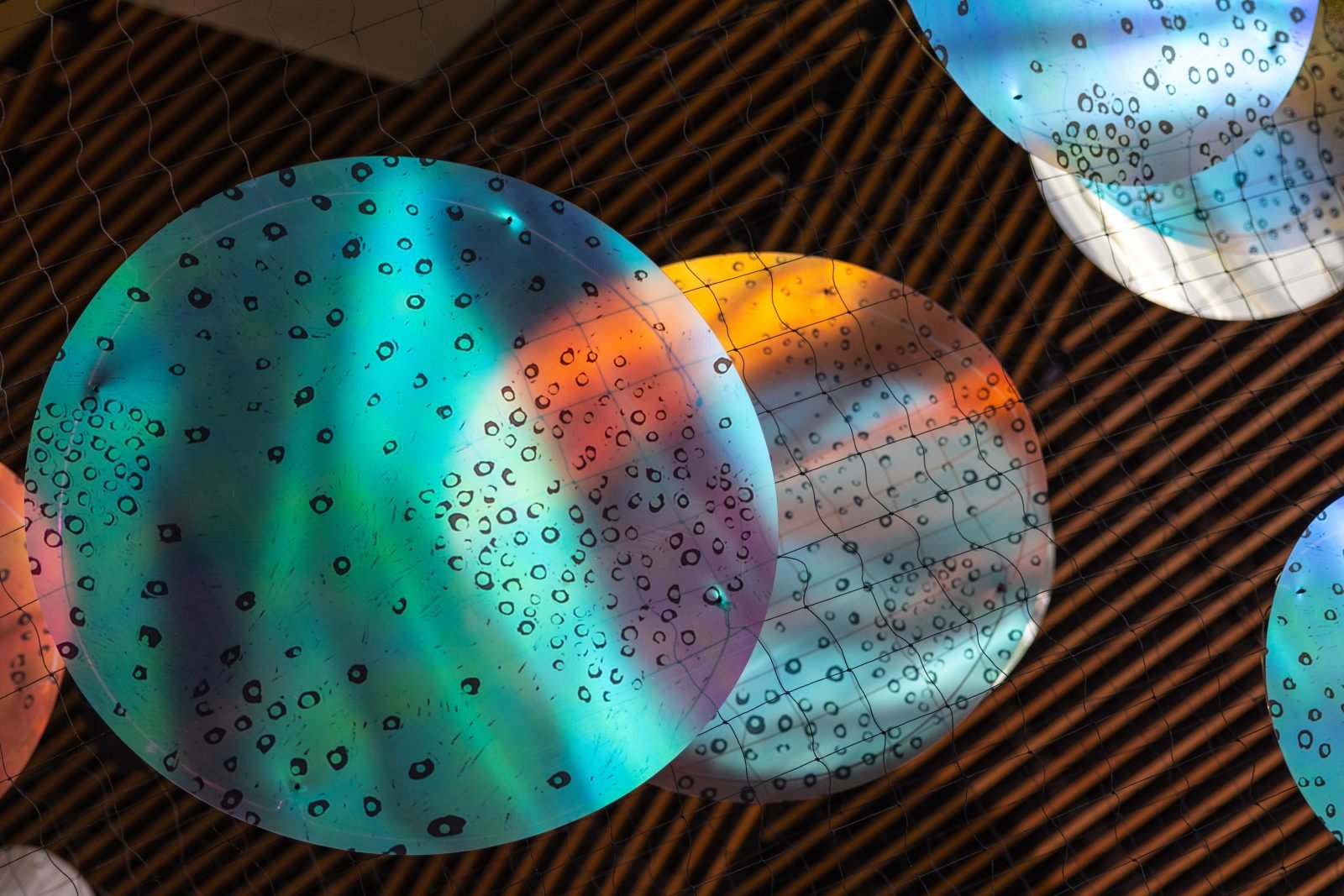

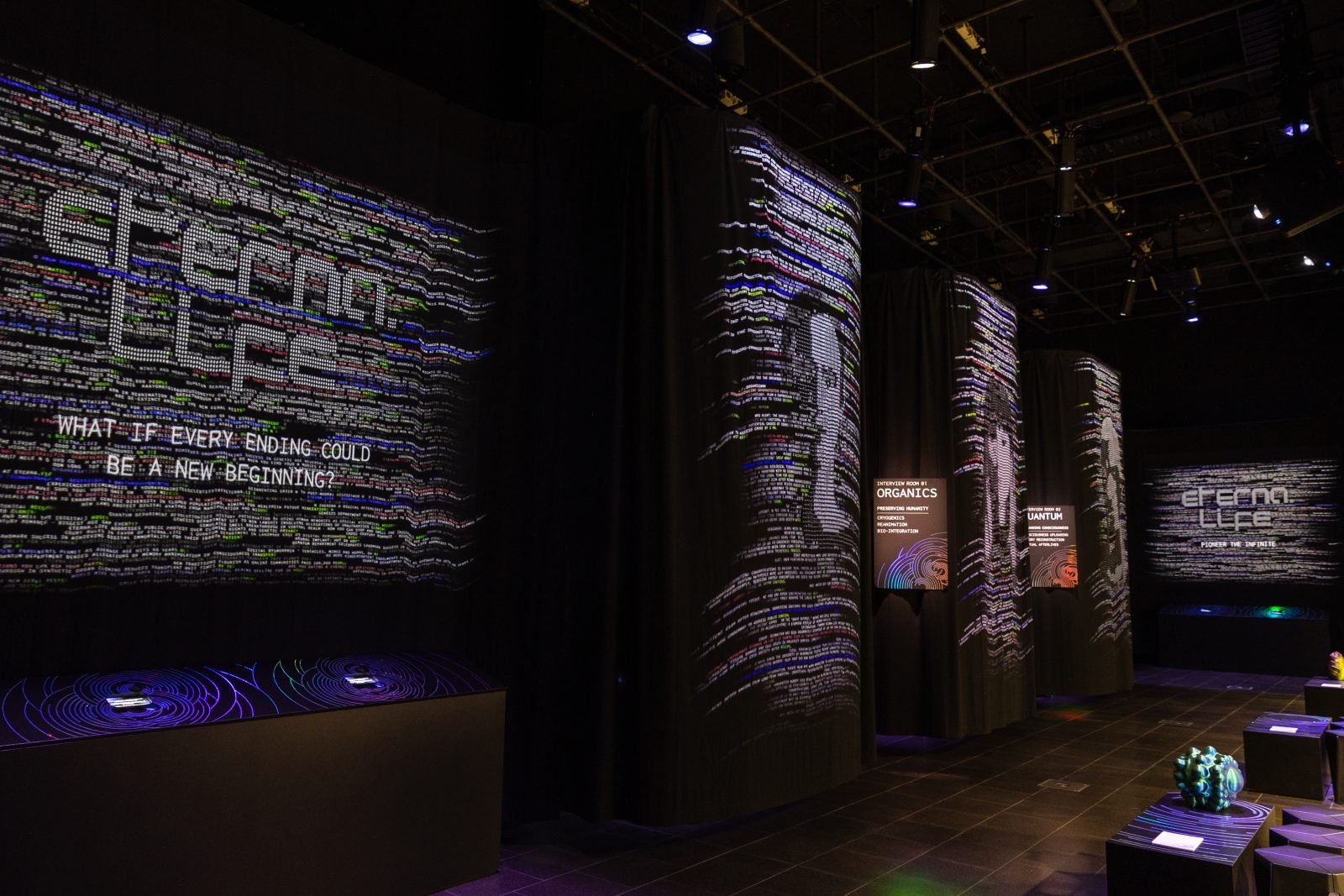

For this gallery, artists Elizabeth Willing and Dirk Yates explored the idea of scent memory. Their artwork, the “Scent Memory Database,” invites visitors to smell scents stored on shelves, each layer holding different aromas that mix to create new combinations.

The chosen scents have been borrowed from the body. For the artist Elizabeth, ‘The breath of the work reminds me of an aunt’s linens, a lovers hair, her hands after cooking their signature dish, his clothes after camping. The artwork gives clues to the scent’s origins, but the content of the memory comes from me, my history, my scent memory database.’ Although curated by the artists, the scents prompt visitors to recall their own scent memories, creating a personal journey through time.

Why is scent such a powerful retrieval cue? And though it is so powerful, is it vulnerable to manipulation?

PhD candidate Hayley Caldwell is based at the Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory ARCIVE at the University of South Australia. Her research uses retrieval cues to investigate how we stabilise and enhance memory in sleep. This may lead to determining actions we can take to improve learning when awake.

Hayley says, ‘smells are the most effective retrieval cues as they are processed more closely than any other sense to the hippocampus, our brain’s memory hub.’ Above the nasal cavity at the base of the brain sits the olfactory bulb. This bulb is a group of cells sensitive to smells. It has a direct connection to the hippocampus and amygdala, key regions of the brain involved in memory and emotion. This makes smell a strong sense for memory recall, but in some ways, it is also a vulnerable sense.

Each time you recall a memory, you’re reconstructing and re-encoding it. Hayley says this is because ‘that memory has to be rewritten to our brain’s long-term storage again.’ This rewriting of memories makes them vulnerable. New information can be incorporated, and the less relevant details can be lost. With this in mind, it poses an interesting question – is it ethical to play with people’s memories? The next time visitors encounter a scent from the exhibition out in the world, they may recall MOD. as part of that memory recall.

According to Hayley, ‘While a lot of us treat memory changes like this as a bad thing, this process of merging new and old memories together is actually a major strength of our memory system. This adaptive “forgetting” often leads to the lessons we learn from our memories becoming generalisable to more situations. More generalisable memories help us build overarching rules and knowledge, which we can quickly and effectively use to navigate the world.’

Read

- The tantalising scent of rain or freshly baked bread: why can certain smells transport us back in time?

- Can you learn in your sleep? Yes and here’s how

- How odour cues help to optimize learning during sleep in a real life-setting

- Here’s why memories come flooding back when you visit places from your past

- The strange science of odour memory

- Remembering the past and imagining the future: Identifying and enhancing the contribution of episodic memory

- Thinking through time from collective memories to collective futures

- Nostalgia: Past, Present and Future

- Is nostalgia a past or future-oriented experience?

- The Future of Memory: Remembering, Imagining, and the Brain

- Emotion experienced during encoding enhances odour retrieval cue effectiveness

- Memories are made by breaking DNA — and fixing it

Watch

Play

Explore

Credits

- Elizabeth Willing Artist

- Dirk Yates Artist and Exhibit Architecture

- Hayley Caldwell Researcher

- Lachlan Turner Lighting