Interested in social issues?

Make it a career with UniSA

Bachelor of Arts (Sociology)

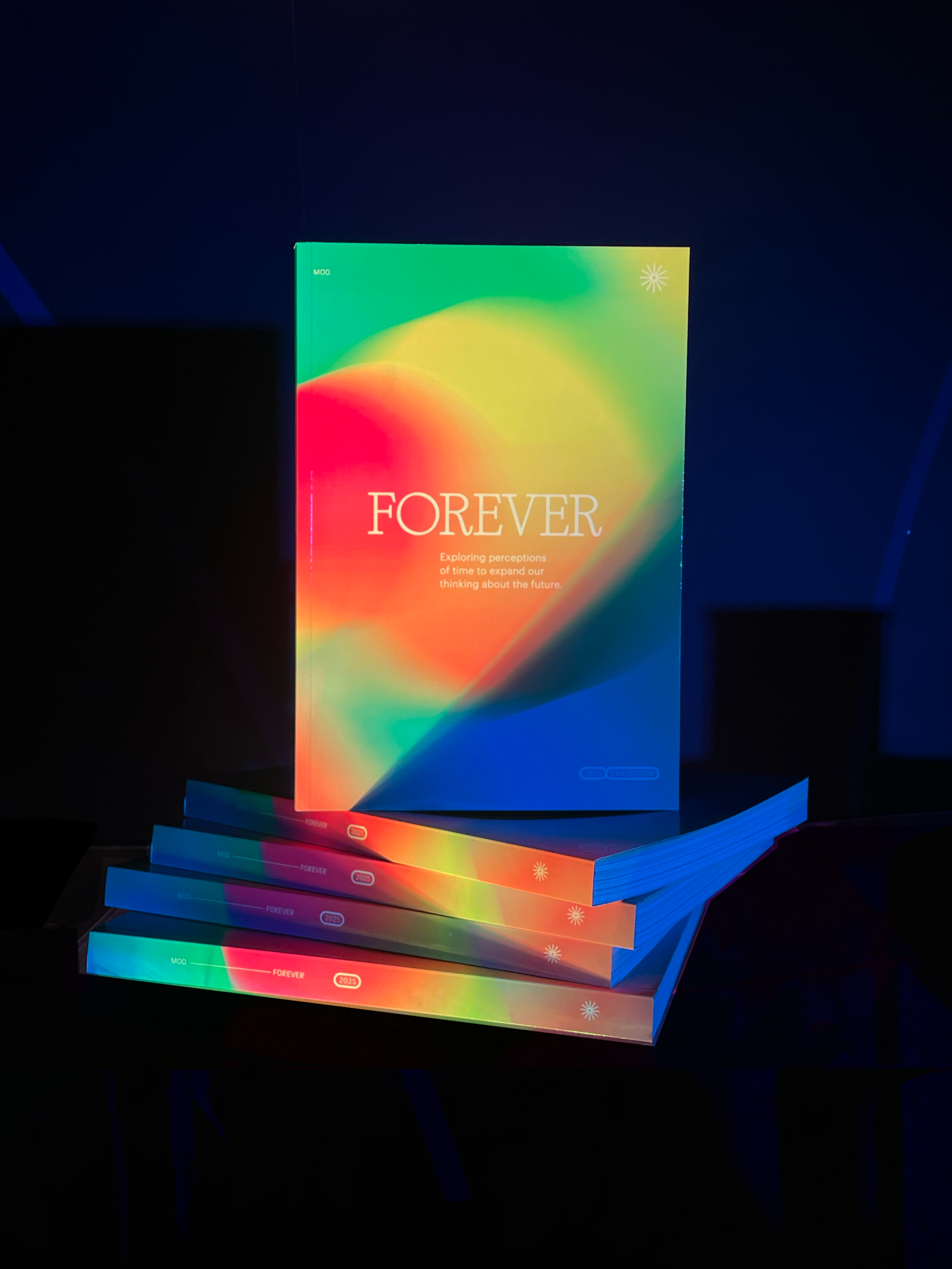

Exhibit Details

Open JanNov 2025

- When does time end? How do we mark endings?

- Delve deeper

Everything has an end. Nothing lasts forever. This too shall pass.

We may often try to avoid thinking about endings, but saying goodbye to people, places and things that are important to us is inevitable.

What happens when time ends and how do we feel about it? How do we mark endings?

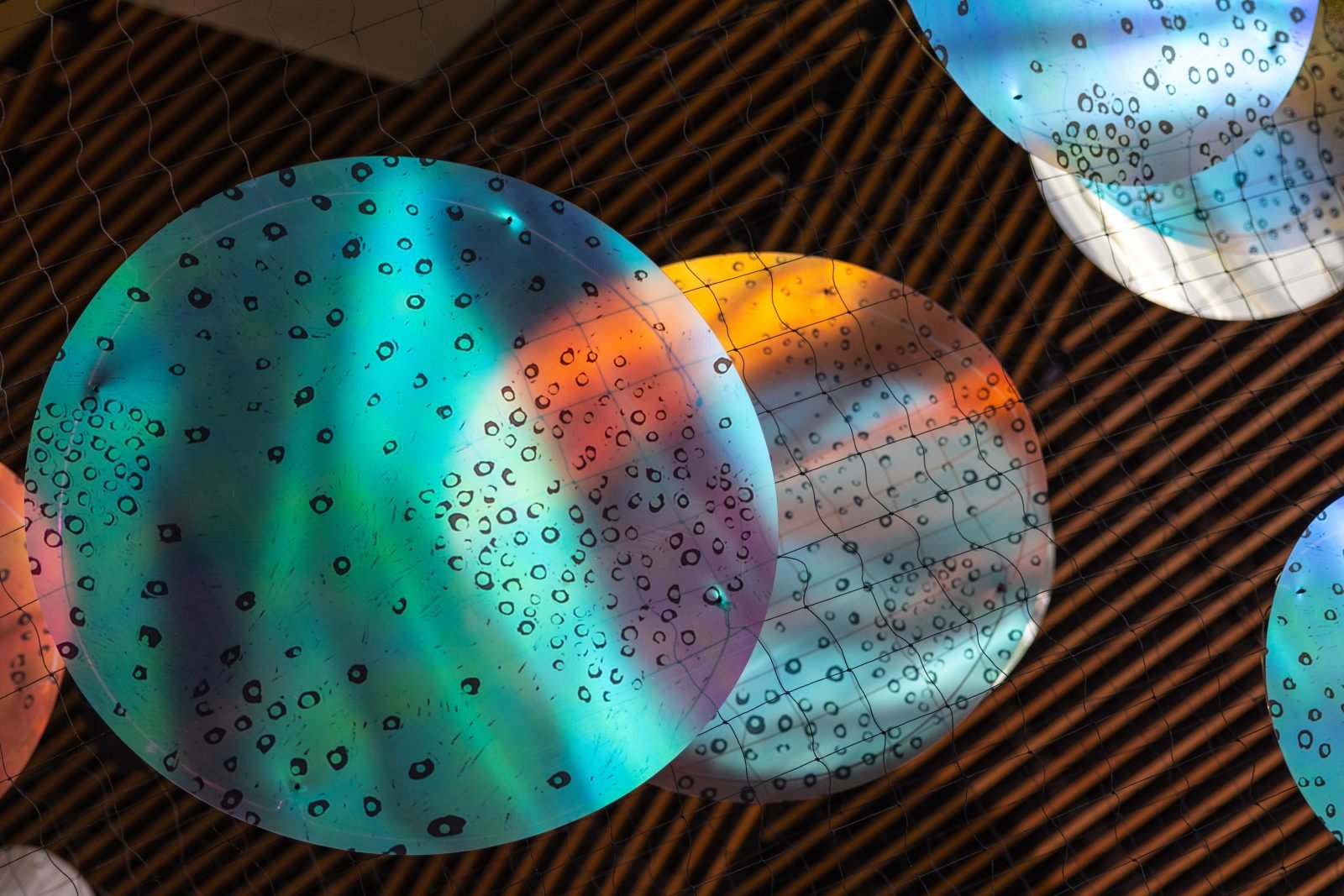

In this gallery space we are inviting visitors to ponder things often not confronted. Our feelings about endings aren’t always clear, and the more we think about it, neither are endings themselves. Consider a range of endings of differing scales, star death, extinction, our own mortality, the ending of languages and a pending endings due to climate change. Are endings cleanly drawn lines set in stone?

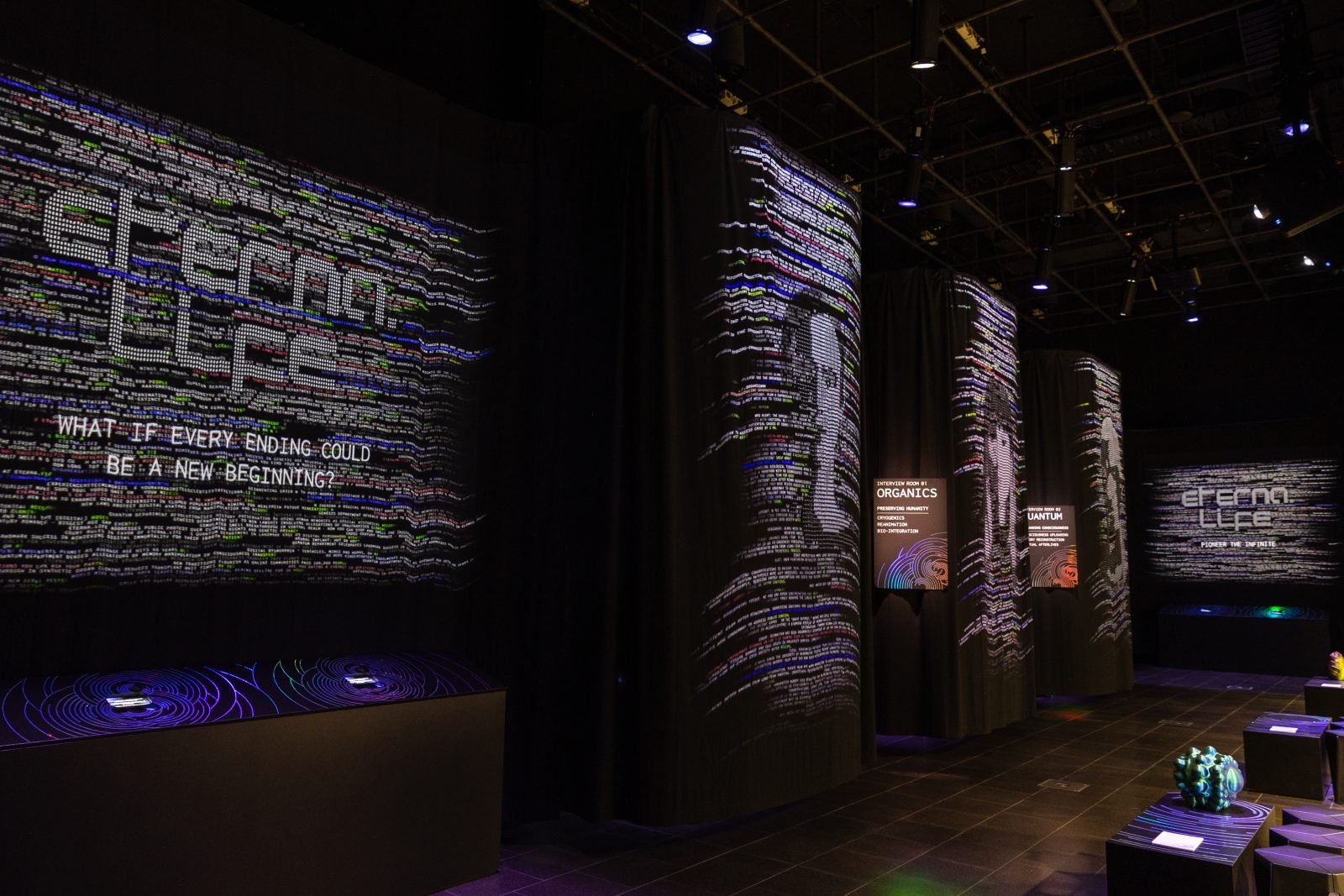

In the gallery space we ask you to respond to a variety of questions prompting your personal opinions in relation to others. Is there such a thing as a good death? Should your digital existence be erased following death? Is your body still your property after you die? Do you believe in an afterlife?

Hear from people who often think about death due to their jobs, personal experiences or research interests. And compare the different ways we may treat the body upon passing.

Endings are rarely clean, definitive lines; they’re more often complex, blurred transitions.

Consider the death of stars. Following a life cycle of a few million to trillion years, when stars run out of nuclear fuel, they die. Some massive stars collapse, exploding as a supernova. Others swell to become red giants, forming a planetary nebula. Upon ending, they generate new forms. The oxygen in our lungs, the calcium in our bones, the iron in our blood, the silicon in our technology, and all the Earth’s gold were formed and released by earlier generations of stars. What seems like a clear endpoint is actually a process of transformation.

Extinction, too, complicates the notion of an absolute end. Species don’t always disappear in an instant. Often, they dwindle over time, leaving traces in genetic relatives or in ecosystems that shift around their absence.

In our own mortality, death also resists simple definition. There are differing medical, ethical, and cultural thresholds for determining when life truly ends. Common definitions can differ from brain activity and heartbeat limits. Even after death, parts of us live on through memories, the people we’ve influenced, and in the biological elements that return to the earth.

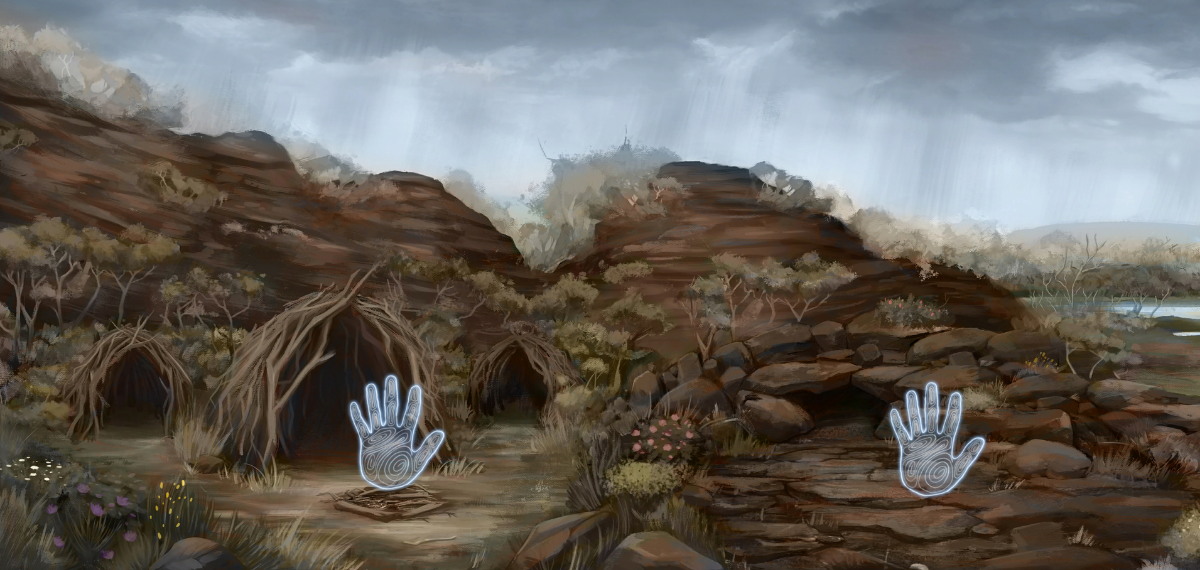

The languages we speak face gradual endings. They can fade from common use as speakers age and younger generations adopt dominant tongues. Yet often languages leave behind fragments in phrases, place names, or cultural practices. Sometimes those languages we think have ended are merely sleeping. We can see this with the revitalisation of the once thought extinct Kaurna language.

Hovering in a space between continuity and crisis, our world attempts to balance through climate change. We’re not yet at an end but face the impending transformation of ecosystems, weather patterns, and ways of life. Each of these endings, rather than a sharp break, is more like a transition or evolution. A shift in form and presence that ripples forward, reshaping what comes next.

Full length interviews can be listened to below:

Read

- DeathTech Research Team

- Digital legacy: how to organise your online life for after you die | Money | The Guardian

- Talk to your family about donation | DonateLife

- Grieving families moving away from traditional funerals despite end to COVID restrictions

Play

- Virtual autopsy

- Spiritfarer – a cozy management game where you play the role of ferrymaster to the deceased

- Death calculator

Listen

- Experience Homebody, recommended for ages 12 up

Explore

Credits

- Junior Major Shroud

- Kansas Bird, Intern Research and conceptual development

- Lachlan Turner Lighting

- John Craig, Intern Soundscape

- Macaulay Library, Cornell Lab of Ornithology Soundscape

- Uncle Moogy, Aboriginal elder and cultural advisor Interview

- Shannon Beresford, End of Life Doula, Your Path Guide Interview

- Bec Lyons, End of Life Doula and Funeral Director Interview

- Rosemary Wanganeen, Griefologist, Healing Centre for Griefology Interview

- Venerable Thich Phước Tấn OAM Interview

- Annamaria Fratini, Social anthropologist Interview

- Stewart Moodie, State Medical Director, DonateLife Research and Interview

- Walls That Talk Decals

- Walls That Talk Graphic design of data display

- Helen’s Mini World Terrarium

- Robert Hart Cosmic Ray Detector