Posted 10 Jul

Words by Sarah Keenihan.

James Walsh is not a police officer, nor a lawyer. But he’s helped develop a piece of technology that could make both these jobs a lot easier.

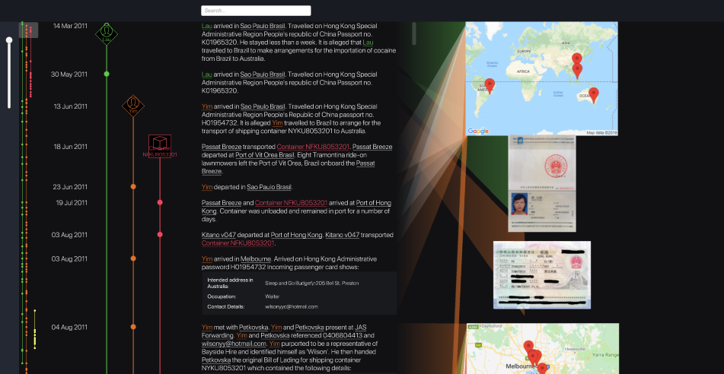

A postdoctoral researcher at UniSA STEM, James collaborated with colleagues to make a tool that can survey all the details of a criminal case, and then spit out an easy-to-grasp snapshot. The technology creates a simple, digestible story to help the viewer understand what has gone on at the scene of a crime.

The tool is based on an approach called Narrative Visualisation, a form of storytelling that uses images to break down and communicate complicated ideas.

The software could save police and law-makers many hours of admin and case transfer time, and is now being developed commercially by Melbourne-based company Genix Ventures.

Endless files, too much detail

Surely policing isn’t that complicated though, is it? Let’s back-peddle a little, and set the scene.

Picture the classic police officer’s desk in an old movie or TV series. A family photo. Dirty coffee cups. Maybe a donut.

Plus piles and piles of manila folders. Inside those files are photos. Evidence and reports from the scene of a crime. Photocopied documents relating to ‘the perp’ (perpetrator) and the victim of the crime. Witness statements. Newspaper clippings. And more.

While most police stations now use digital filing rather than physical folders to help them manage case materials, there’s still a huge amount of information to wade through when reviewing crime – particularly when you need to bring a colleague up to date quickly, or brief a legal team about a case.

“Police tell us it can take up to 400 hours – more than two months work for one person – to prepare the document they used to brief a legal team, something called the ‘statement of facts’,” James said.

“And so we developed the tool to sort through all the digital case materials already on file, and present the key information quickly and accurately.”

The tool uses filed materials to create a snapshot of a crime at the push of a button, ready to be presented to other police or lawyers in an hour or less.

The rest of the detailed case information is not lost – it just sits in the background, ready to be accessed as needs arise later in the investigation or trial process.

What does the snapshot actually look like?

James said the software works through focusing on key events of a case, and by identifying a subject, a verb and an object for each one.

“So as a simple example, imagine you’ve got a person called Alex, who shot a person called Taylor,” James said.

“This would be presented as one event in the snapshot, and connected to other major events in a timeline.”

Here, Alex is the subject, Taylor is the object, and the action is the shooting.

Perhaps the next event might have been that Alex ran down a laneway, and threw the gun into a drain. They then hopped into a car their cousin was driving.

After viewing the main narrative snapshot of these key events, later police or lawyers considering the case might decide to zoom in on Alex, and find extra information. They could click through to look at the file containing Alex’s passport, and see an arrival in Australia one month earlier from Canada. They could find the escape car registration number, as told by a witness to a police offer and added as a documented piece of evidence in the case. Neither of those pieces if information is critical in the initial view, but could be vital in later determining who else needs to be questioned, for example.

Like any kind of tool that relies on data, the snapshot is only ever as good as the primary information filed in the first place. So this approach certainly doesn’t take away from the need for police to keep collecting evidence as thoroughly as they always have.

“The system we developed works with the system the police are already using to label and store all the evidence and information they have for each case,” James said.

But wait, there’s more

Narrative Visualisation could be useful in many applications other than just managing police prosecutions and court cases.

“It’s useful in any scenario that is complicated but needs to be summarised for effective communication between people involved,” James said.

“So even in things like patient handovers in hospitals, where nurses and doctors on a new shift need be brought up to speed really quickly on the health of someone who came into ICU during the night after a car crash.”

It’s a good example of human skills being combined with technology for an efficient outcome.

UniSA’s work on the Narrative Visualisation tool took place in collaboration with the Data to Decisions Cooperative Research Centre.