Posted 17 Nov

Words by Sarah Keenihan.

Artists make art, right? Paintings. Drawings. Sculptures. Things that exist in the physical world.

But UniSA PhD candidate Thomas Folber says art isn’t just about the end point.

“Art is about going into the wilderness,” he says. “You know, when you go for a walk in the bush and you get off the trail – that’s the point at which there’s an element of discovery.”

Thomas is an artist who likes to work with glitches.

You might be familiar with the term “glitch” as a temporary flaw or mistake in an operating system or piece of equipment. But glitch art treats the glitch not as an error per se, but instead as a means to create and explore.

As an artist, Thomas goes to places he’s not supposed to be. He uses techniques that are unconventional. He extracts his experiences to create something new.

Glitch art explores how you get somewhere, not just that fact that you arrive. It puts you up close with a process, and cements it in a time and a space.

When digital meets physical

Thomas started his artistic life as someone who liked to make pictures. His first degree was a Bachelor of Visual Arts, majoring in painting.

“Many glitch artists work only in the digital realm,” Thomas says. “But I have a love-hate relationship with digital.”

“I like to make things with my hands, and so I tend to use digital technology as more of a tool than a platform. My preference is always to bring it back into a material object,” he says.

What does interest Thomas about technology is the notion that digital operating systems are increasingly invisible. Tech companies refine their products so you don’t so much notice the device (such as your phone), as long as it delivers the capability you need (like being able to message a friend, or check your email).

“Part of what I’m looking at in my research is the idea that digital technology obscures all these inner workings that are going on beneath the surface,” Thomas says.

To reveal those processes, he seeks ways to convert digital information into a physical form – even when that information has not been designed to be taken out of the technical format.

“When you make a translation to allow a digital file to become a physical object, the process can introduce elements you can’t control,” he says. “This is when the glitches may occur.”

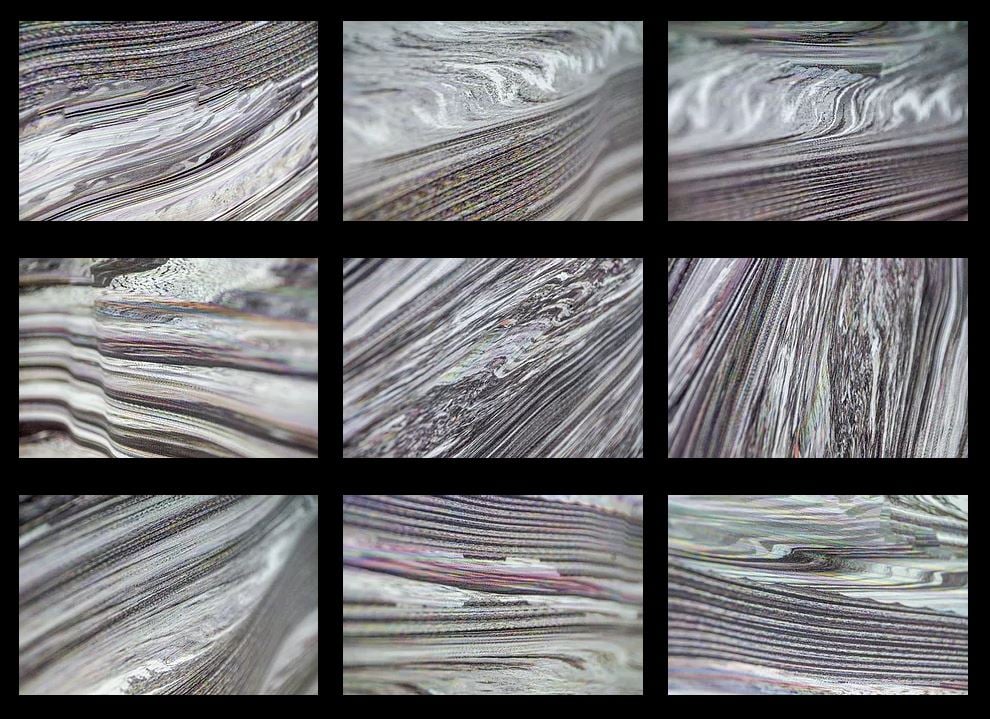

Some of Thomas’ work is produced using a large flatbed printer, with slabs of glass, wood and aluminium as the printing surface.

“This allows me to introduce a new scale, as well as the glitch,” he explains. “Rather than viewing a digital image that’s 20cm across on a screen, you can make it two metres wide in the physical world.”

“The ink is almost like an acrylic paint; it has a real thickness and texture to it,” Thomas adds.

And so the artworks become three dimensional, and tangible – including the glitches.

Threads through work

Thomas uses the research he’s conducted as part of his PhD to constrain his work into key threads.

One collection is called Wasteland, something that started with him thinking about what it feels like to be wandering around inside a computer. What sort of a place is it?

“These works start with images of landscapes, and I apply glitches to create uncanny versions,” Thomas says. “I use the term ‘parasitical’ to describe these images, as they need a host; they have to start with an image to corrupt.”

In biology, a parasite is a living creature that lives on or in another animal.

Thomas then takes the glitched landscapes, and plays further.

“I convert the images to different formats, and bring them off the computer,” he says. “I print them, and then photograph them, and then put them back on the computer again – going back and forth, on and off digital.”

Thomas calls this thread Drift, after an artistic strategy originally named in French as ‘dérive”.

“Dérive was a practice primarily active in the 1960s and 1970s, where groups of people would wander through urban environments in unconventional ways to better understand the places they existed in,” Thomas says.

“And that’s what I feel like I’m doing, except I’m drifting in a virtual space, not a city,” Thomas says.

A third thread is named Residue, in which Thomas collects audio and video recordings during the process of making a piece of art, and then feeds those files back to disrupt the original objects.

“Every time you do this it leaves a residue on the image,” he says.

“And that’s why glitch is an exciting way to work as an artist, because you never really know what’s going to happen.”

Glitches aren’t always a bad thing.