Posted 15 Sep

With emerging technology becoming a large part of our everyday lives, our capabilities are more enhanced. Where do we draw the line? What do we feel comfortable with? September’s Ethos event considered the ethics of augmenting humans, including questions about using external technologies – like our phones – to enhance ourselves more broadly. Ethos aims to foster a culture of ethical questioning amongst students, researchers, and the public.

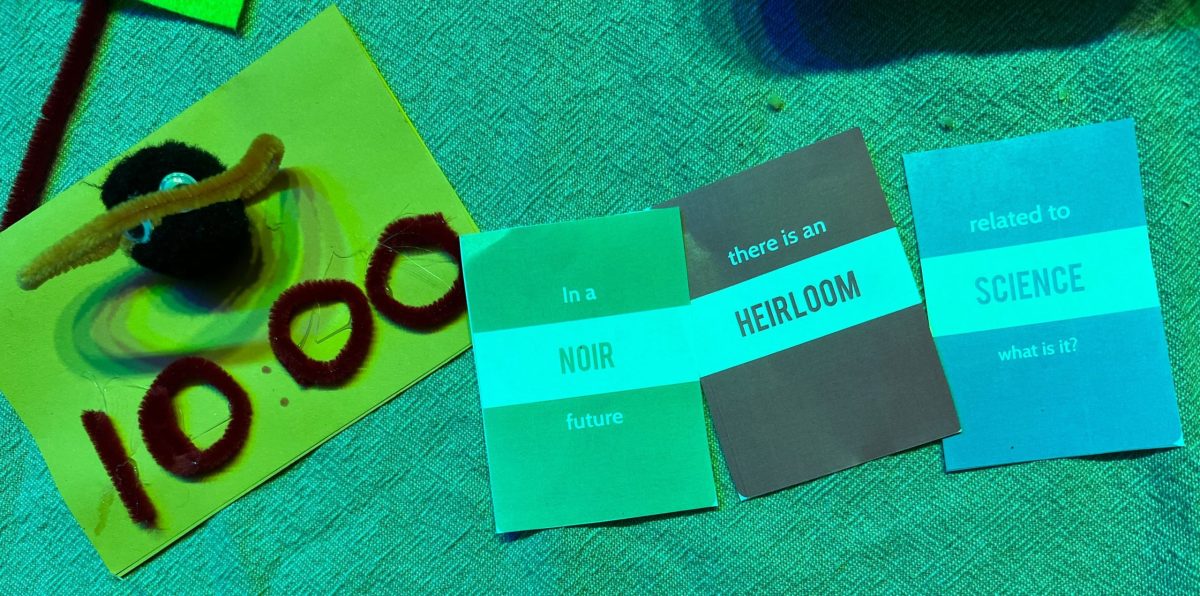

The evening kicked off with an activity facilitated by host Dr. Debbie Devis. Participants created objects to enhance our capabilities with various arts and crafts supplies. The catch though, was that their object had to respond to a “Thing from the Future” – a set of cards which dealt them a proposed future scenario.

So what objects did our participants invent for augmenting humans of the future?

Results from the activity showed that while there were some positive inventions – such as an ‘enlightenment kit’, providing instant inspiration and connection to spiritual realms on the go – there was an abundance of ‘worst case scenario’ inventions. For example, one guest invented a camera that uses AI technology to filter out any unhappy or unpleasant sights, as well as another guest who invented a countdown for an atomic bomb yet to go off. And my personal favourite, a monument of resistance against climate change built on a raft to combat rising water levels. Ultimately the activity highlighted a common fear for the future, perhaps suggesting that the technology we have now has left us feeling unprepared. But do we feel comfortable augmenting humans even more to combat these proposed futures?

We discovered that talking about the ethics of augmenting humans can be quite daunting. To guide us through this Devis asked Eric Zhengzheng Wang, Dr Bella Bower, and Associate Professor Carolyn Semmler to delve deeper. After the discussion panel provided our guests with some stimulating prompts for group conversation, we shared our thoughts about these ethical questions and insights.

By now, most of us have heard about Chat GPT. We are seeing a rise in these AI chatbots within schools and universities as they have become a popular tool to assist students with their assignments. Who doesn’t love the idea of an assignment that basically writes itself? Using these AI ‘tools’ to enhance our education experience can sometimes be exploited though, and so Eric Wang gives us some insight into how these technologies are being used to enhance students’ unique capabilities in schools.

Wang introduced us to his research by discussing the various ways AI personalises education. For Wang, tailored schooling experiences support students unique capabilities. This is achieved through adaptive learning. AI learns which tasks to assign to students based on their learning outcomes, creating more suitable responses. In fact, this system is so efficient that AI adapts to student responses in real time. Almost stepping in as a “teacher” or “classmate”. Alongside this, AI also provides feedback to teachers. It monitors groups of students to determine their levels of collaboration, communication, and other group dynamics. Imagine if group assignments were arranged based on student compatibility!

Augmenting our learning and thinking is not new, we have been doing this for thousands of years. As technology advances, so do we. But are we entering uncharted territory when it comes to augmenting humans through AI? As mentioned above, Wang’s research contributes to AI software that’s more adaptive and tailored than ever before. This highlights a shift from making AI work for us, to working alongside AI, or even considering it a teammate. With this in mind, is it safe to say we have reached AI consciousness? Associate Professor Carolyn Semmler enlightens us by introducing us to her research. In terms of actually defining consciousness, Semmler says that it’s “an unending debate – philosophers have been trying to define it for what feels like tens of hundreds of years”. If we struggle to define human consciousness, it seems unlikely that we could agree on AI consciousness.

So, how much can we trust AI from an ethical perspective? For Semmler, we should be considering what might happen once we include AI in our moral circle. Therefore, what legislation would need to be in place? Thinking back to Wang’s research, what happens if there is conflict between a human (or student in Wang’s case) and AI? Therefore, Semmler proposes a world where we might need professional legal bodies to mitigate these issues. In that case we would have to consider who’s rights would come first, human or AI?

Semmler stresses the importance of these questions, and how we should be thinking about them more often. For Semmler, education on AI should be aimed at young people to ensure better protection whilst using AI. If these issues are mitigated before we continue to augmenting humans, then perhaps we could responsibly and ethically enjoy the benefits of using AI. Linking back to Wang’s research again, a major component of his project is to assist students in identifying the bias of AI. For Wang, people need to be able to ethically assess their cooperation and collaboration with AI. This particularly important for our youth, as Wang’s research suggests that we will be working alongside AI in the near future.

So, now we know that we can augment our education and thinking through the use of AI, but did you know that our environment can augment us in many ways too? I sure didn’t. Dr Bella Bower introduces us to her exciting research and delves into this topic a little deeper.

According to Bower, we spend 80-90% of our lives inside buildings (yikes), yet there isn’t a whole lot of research on how building design can affect our concentration, attention and emotion regulation (big yikes). However, Bower’s previous research shows that being in smaller spaces stimulates brain activity associated with concentration. Therefore, being in a large space or with a large group of people weakens your ability to concentrate well. This might explain the design of classrooms, office spaces, and so on.

But what about spaces that are not designed with our capabilities in mind?

Bower explains that buildings aren’t always designed with our needs and capabilities in mind. If the building design of your workplace makes you feel stressed there’s little you can do. Bower demonstrates a few ways we can combat this. For example, going outside on your breaks at work can reduce feelings of stress compared to sitting in the lunch room. Bower even suggested the use of smartwatches as a strategy, as they prompt you to move your body throughout the day. In a perfect world, we could demolish and re-build spaces to enhance our capabilities. But of course, it would be incredibly unethical to do so. However, Bower hopes that her research leads to more ethical building design in the future. For Bower, like the guidelines in place for our physical safety, there needs to be guidelines in place to protect our mental wellness.

As mentioned throughout the discussion, we augment ourselves everyday through using technology and the environments we are in. It appears that most of the time we are completely unaware of it too! Discussions with guests reveal that not everyone feels comfortable having little to no autonomy over the augmentation of our psyche. For example, some guests highlighted that this is especially noticeable in casinos. For example, the strategic use of colour, lack of windows and clocks, and distracting noises are all examples of this. Linking back to our discussion about AI, did you know that even poker machines use AI? Utilising adaptive, real time technology, poker machines can now tailor each game to the players responses.

Above all, concerns raised by our panellists and guests suggest a call to action. Better ethical guidelines are needed to ensure we have more autonomy over augmenting our bodies.

Ethos is made possible with funding through the Deputy Vice Chancellor of Research and Enterprise. We hold Ethos events regularly at MOD. You can find more details here.

Renée Pastore was the rapporteur for this event and is a moderator at MOD.