Posted 24 Apr

Written by Laura Phan

It’s no question that countless people across the planet have had plans derailed amidst this pandemic-fuelled global disruption, and PhD graduates are no different. From skipping out on walks across the graduation stage for downloaded PDF parchments and defending 100,000-word theses in bedrooms via video call, this PhD Celebration blog series for LIFE INTERRUPTED will celebrate the soon-to-be and newly graduated researchers that tackle the big unknowns of how we work, play, function, live, and exist. We invite visitors to expand the way you view and think about the world by hearing what matters and why from the researchers themselves. For those interested in neuroscience, this instalment is for you.

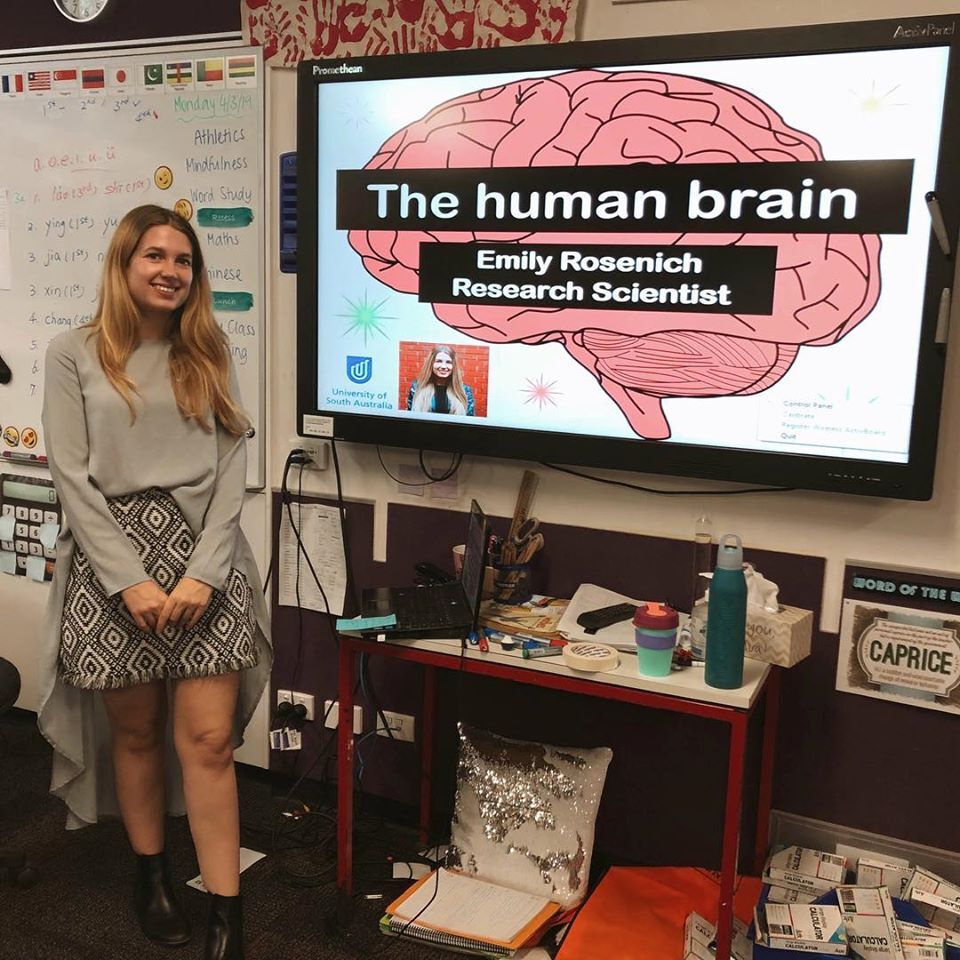

Emily Rosenich is a clinical neuroscientist and PhD student with the Allied Health and Human Performance unit at UniSA. As a finishing candidate, Emily is gearing up to submit their thesis in the next coming weeks, and we want you to join in on the celebration. When she is not busy being an avid science enthusiast and outspoken voice in encouraging girls to enter the world of STEM, Emily loves collecting second-hand vinyls (and is always on the lookout for Frank Sinatra records to add to a growing collection).

Strokes. An interruption in blood flow to the brain, usually through a blood clot, but sometimes from haemorrhaged blood vessels. Basically, during a stroke, blood is not getting where it needs to be, which can result in pretty severe impairments to how we think (cognition), move (motor function), feel (sensation), and communicate (language). Every minute that a stroke is left untreated, roughly 2 million brain cells die – time is brain, literally!

Adding to the ‘trio of death’ in Australia where heart disease and dementia/Alzheimer’s disease respectively take first and second place, cerebrovascular diseases (including stroke) takes third place in Australia for leading cause of death and burden of disability (the collective amount of healthy years lost as a result of a disease or condition). Not only debilitating at the systemic level where healthcare systems and economies bear the brunt, strokes can be equally (if not more) debilitating at the individual level. The good news is that a whopping 80% of strokes are preventable!

Revolutionary medical advances have seen the ability to dissolve and even mechanically extract blood clots from the brain which has decreased mortality significantly. However, the next big problem is that although medical intervention is saving more lives, people are often left with stroke-induced impairments and disabilities, most of which can be hugely disruptive and debilitating to everyday life. It’s easy to take for granted the ability to memorise thoughts or perform daily activities like walking, showering, dressing, and eating – many of which can be lost in a short, life-changing moment. For example, in an older cohort, up to 30% of people who have a stroke will then in the next year go on to develop dementia. For a younger demographic, cognitive impairments can really disrupt someone’s working life, their ability to return to work, and engage in meaningful activities.

When the numbers say that 1 in 6 Australians will have a stroke in their lifetime, chances are you know someone who has had a stroke, have had one yourself, or may have one in the future. And it may come as a surprise, but it’s a huge misconception that strokes only happen to elderly people. While it’s true that increased age is a risk factor for stroke, that doesn’t change the fact that around 30% of stroke survivors are of working age (under the age of 65).

Have you ever thought about why some people recover differently than others after they’ve had a stroke? This is exactly what Emily delved into during her PhD, and the answer may lie within a concept called ‘cognitive reserve’ that’s been on neuroscientists’ radars since the late 80’s. Originally developed to help explain why some people perform better than others in the face of Alzheimer’s disease, and later on multiple sclerosis and traumatic brain injuries, cognitive reserve was yet to be explored in the context of stroke – until now.

Cognitive reserve is developed throughout your entire life and encompasses a whole range of determinants like social engagement and intellectual attainment. Emily suggests thinking of it like a savings account in your ‘brain bank’, where you can keep a reserve of neural resources to withdraw from later if needed. Cognitive reserve is built by engaging in physically, socially, and mentally stimulating activities like learning. In fact, reading this is currently building your cognitive reserve, which is valuable currency because it can moderate the effects of brain pathology on clinical outcomes, like how well people can recover from a stroke.

It can be a promising tool in aiding prediction of recovery prognoses, and even informing rehabilitation decisions. That’s a big deal when the outcomes can determine a large chunk of people’s physical and emotional wellbeing. While stroke-specific measures like stroke size can provide similar prognostic information, these measures are less cost-effective and don’t take on as much of a holistic, person-centred approach to the prediction of recovery. These may be important factors to take into consideration heading into the future of healthcare.

In terms of clinical application for the future, Emily hopes to see a broader focus on all domains of recovery, particularly cognitive recovery, rather than the traditional focus on motor function in the field of stroke recovery. This includes opening up more space for person-centred rehabilitation, which could increase rehabilitation participation, by integrating more activities that are meaningful to people, and having more resources put into the prevention of post-stroke dementia.

Since we can’t rely on brain tissue to repair itself like skin after a papercut, to harness the protective effects of cognitive reserve starting today, Emily recommends depositing valuable currency into your brain bank by pursuing a range of complex mental and lifestyle activities across your lifespan. The recommendations are simple – consistently do what you enjoy (how good is that?!), shake it up by trying new activities, and when possible, do those activities in a group. Simply put, anything that challenges or stimulates the brain is invaluable for building brain health. Even better, it’s never too late to start building your cognitive reserve. Despite the pathological burden that a stroke or other brain injury may cause, so long as you have a brain, cognitive reserve can continue to develop with age.

Want to find some answers in a world of unknowns? Got a topic you’re keen on delving deeper into? Emily’s tip for anyone who wants to pursue research or a career in academia is don’t be afraid to ask! If there’s someone whose research really inspires or fascinates you, reach out to them and ask about how you can get involved. Asking to learn more about someone’s research and whether they have opportunities for you to get involved through a polite email goes a long way.

If heading down the road of research sounds like a path you’d like to take, UniSA has a range of research degrees for STEM, health, art, and social science enthusiasts that you can explore here.

Connect with Emily on Twitter @ekrosenich.