Do you want to understand human perception?

Exhibit Details

Open JanNov 2023

- In Brief

- Want More?

- Accessible Resources

- Photos of exhibit

This exhibit was part of the exhibition FLEX which ran from 17 January – 24 November 2023.

Every day we get out of bed and we make decisions. We decide how risky things are based on our perception of the activity. And we decide how we feel based on the pain we are feeling.

We trust our brains to tell us if things are safe, or if something hurts. But perhaps all is not as it seems. How easily fooled are we?

The body and mind work together to make us feel pain. Test how by taking a seat in our pain chair. Will you brave the pain like the 50,000 people that came before you? Exhibited in our first exhibition MOD.IFY as part of the Feeling Human exhibit, these chairs were so popular we had to bring them back.

Can pain be shaped? Design your own 3D model and show us just how spiky a bee sting or broken wrist feel to you.

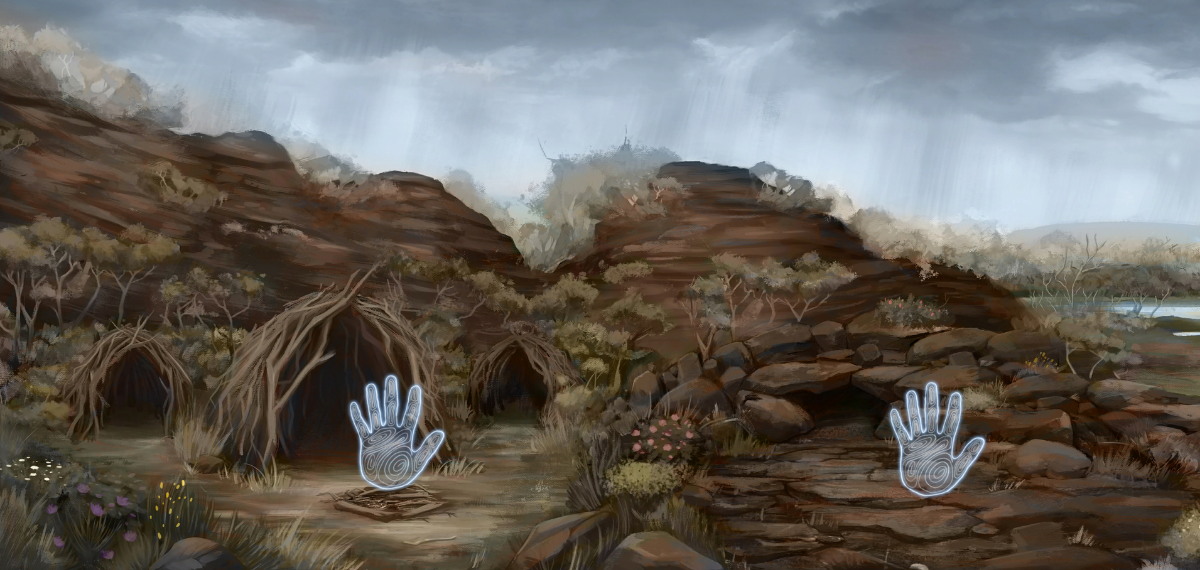

Sit back in our sound chairs and hear from Ngangkari healers about their experiences with chronic pain, and healing with their hands.

Speaking of hands, why don’t you put yours inside our MIRAGE machine? Watch as the natural assumptions about your body that your brain makes are manipulated.

Pain is one thing, but what about your risk of death. Everyday we engage in activities that are risky. What is riskier, sky diving or climbing Mt Everest? See how close your perceptions are.

Warning: This exhibit explores perceptions of pain and may cause discomfort for some people. Parental guidance is recommended. An element of the exhibit emits an electric shock which may interfere with implanted electrical devices such as pacemakers, all types of defibrillators, deep brain or spinal cord stimulators. This exhibit also uses lighting effects that may trigger a photosensitive reaction.

How good are we at figuring out what’s risky?

How do the body and mind work together to make us feel pain?

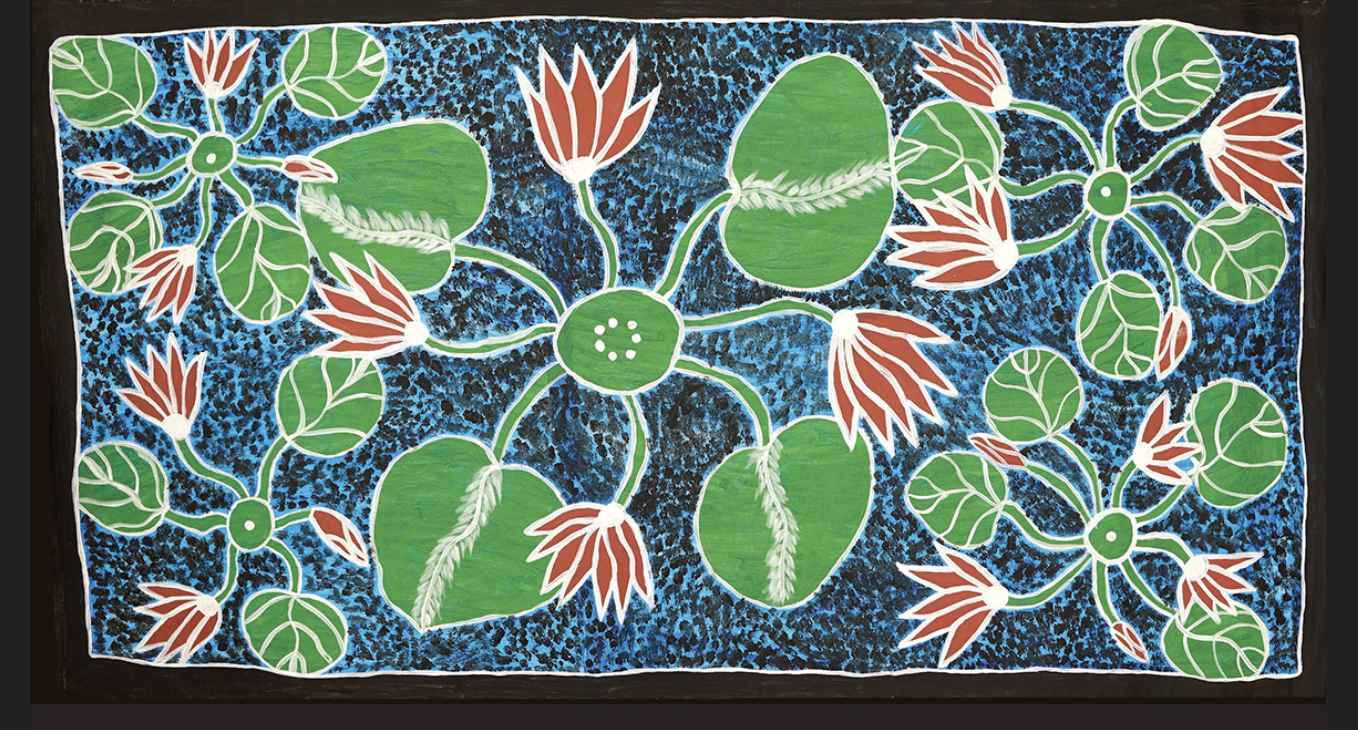

How is pain culturally dependent?

Now we know that pain is highly dependent on context, how does culture play a part in this?

Discover More

Participate:

Watch:

Read:

- Research by UniSA about estimating everyday risk

- Read how surfers perceive the risk of sharks

- Explore the expression of pain through creative processes and visualisation strategies

Listen:

Transcript for Pushing Perception here.

Transcript of the NPY Ngangkari Traditional Healers here.

Audio description:

Credits

- Professor Lorimer Moseley Research

- Dr Tasha Stanton Research

- Dr Hannah Keage Research

- Associate Professor Tobias Loetscher Research

- Ian Gwilt Research

- Adam Droguemueller Research

- Aaron Davis Research

- Josephine Mick NPY Women's Council

- Pantjiti Lewis NPY Women's Council

- Alison Carroll NPY Women's Council

- Uti Kulintjaku Collective NPY Women's Council

- Exhibition Studios Gallery Design and Build